|

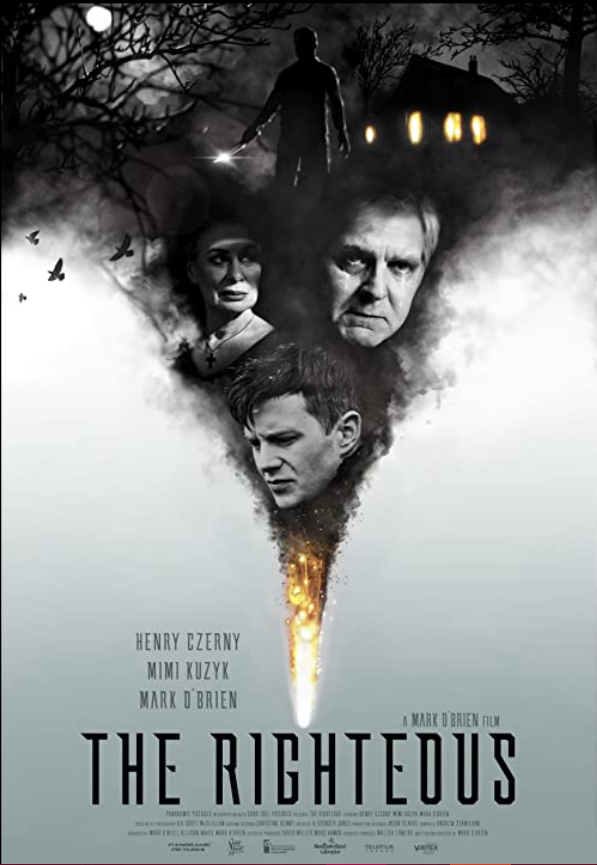

Originally published on Elements of Madness. If you’re into Southern Gothic literature, you’ll go nuts over Mark O’Brien’s feature directorial debut, The Righteous, which screened at the Fantasia International Film Festival earlier this month. Granted, it was filmed in Canada and not the American South, but it sure does capture the dread, madness, religious anxiety, supernatural freakishness, and overall darkness of the genre. The Righteous tells the tale of ex-priest Frederic (Henry Czerny) and his wife, Ethel (Mimi Kuzyk), who are trying to make sense of their lives after they lose their only daughter. The couple’s mourning process comes to a halt one night when a stranger, Aaron (Mark O’Brien), shows up outside their home with a sprained ankle. Aside from his irreverent vocabulary and general secretiveness, Aaron is a harmless, mild-mannered kid. However, his presence casts a haunting shadow over Frederic and Ethel’s household, a shadow that will change their lives forever. The Righteous feels like a play adapted into a movie, in a good way. Much like a play adaptation, it’s driven by dialogue and performance. Most of the action is confined to one space, like a play, and the most intense dialogue takes place around Frederic and Ethel’s kitchen table. And, like a live play, The Righteous boasts its performative aspects rather than trying to conceal them. From the moment the movie starts, it lets us know that the story to follow will be a staged performance and not a mirror reflection of reality. The very first image we see after the title credits is Frederic praying on his knees in a dark, empty, stage-like space under the harsh glow of a spotlight. Unlike other narrative films, where we’re supposed to forget that we’re watching a movie and buy into the idea that the characters could be real, The Righteous uses this opening shot to let us know that this is, without a doubt, a performance. The Righteous wants us to know that we’re watching actors who have put on makeup and costumes to represent something other than themselves. The movie is also in black and white, which makes the story feel even more distanced from reality. While some might say that this performative aspect just makes the movie more artsy, it definitely serves a purpose. First, it makes The Righteous feel otherworldly and, therefore, even more eerie and frightening. Even the skeptics can’t deny the tangible occult presence looming over Frederic’s life. Second, and almost counterintuitively, the self-aware performativity makes the morals of the story more applicable to our own reality. The characters on screen aren’t supposed to represent real people in real situations, but universal ideas. The Righteous takes on the weight and importance of a myth or legend, as if it were a story invented to explain our world via characters that represent universal truths about humankind. The gloominess that so visibly characterizes the story makes it feel like a spooky tale that was invented to teach people a lesson. In a way, The Righteous is like a 21st century morality play. And yet, the characters and conflicts in The Righteous aren’t so universal that they come across oversimplified and shallow. In fact, the emotional conflicts in the story are quite complex, and there’s plenty of character and conflict building packed into every possible second of the film. The Righteous is the kind of movie where every line, every shot, and every transition is spooky and meaningful, engaging our attention as we anxiously wait for the characters to reveal their secrets. The story is clothed in total darkness and dread, and except for one tender scene in which Frederic and Ethel reminisce about when they met, The Righteous is tense from start to finish. Although there’s not a lot of action, and the characters don’t venture far beyond Frederic and Ethel’s home, The Righteous is so tense that it doesn’t feel slow. It’s not the kind of tension you feel in a jump-scare movie, but more of an overall existential dread that just settles down over Frederic’s entire world. The Righteous is also filled with intimate conversations that allow the cast to shine. When Aaron jumps into an elaborate story during a one-on-one conversation with Frederic, O’Brien totally commands the screen and takes control of the narrative. He captivates both Frederic and the audience with his haunting, uncanny tale. O’Brien can play both charming and suspicious, which is the perfect combination for Aaron. However, Aaron is definitely out of place in Frederic and Ethel’s quiet, religious world, and, at times, O’Brien’s approach to the dialogue is so different from Czerny’s that it feels like the movie has transitioned into a different genre. While these little blips are awkward, they don’t detract too much from the film overall. Czerny has his role of the guilt-plagued man down pat, and his slow-burning, self-destructive battle plays out at just the right pace. He clearly studied his part well, and the role gives him the chance to show off a wide emotional range. The only problem with Frederic is that he’s just the slightest bit too sympathetic. This is the result of both Czerny’s performance and the script, which both focus more on Frederic’s role as a victim of oppressive religious guilt rather than his role as a victimizer. However, you could also argue that the reason the story is so powerful is because Frederic is too sympathetic for us to suspect him of wrongdoing. This reflects how seemingly harmless people in positions of power can abuse that power and get away with it. Those who haven’t been through the emotional trauma of religious guilt may not find Frederic sympathetic at all. In the end, this troublesome protagonist (or, perhaps, antagonist) opens the door to lots of debate and discussion, which is the best thing that a film can do.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|