|

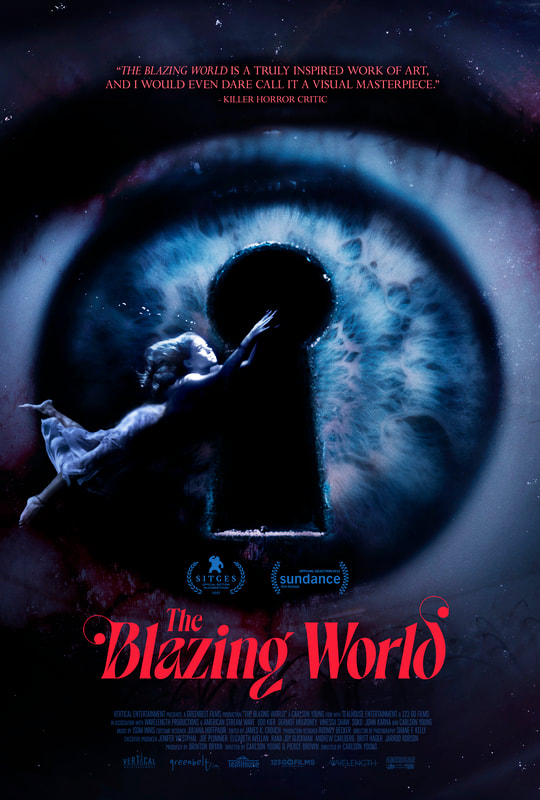

Content Warning: The Blazing World involves heavy subject matters that may be triggering to some viewers, including self-harm. These issues are briefly discussed in the following review. The fantasy genre is endlessly attractive. It can enchant us with whimsical imagery and inspire us with dynamic characters who set off on adventurous quests. Fantasy lets us escape into mystical worlds with different rules than our own — but usually, those worlds reveal some kind of universal truth. In The Blazing World, a college student named Margaret Winter (played by Carlson Young, who also wrote and directed the movie) enters a fantasy world that reflects the inner workings of her subconscious mind. Her mystical journey through this world allows her to process grief that she’s been bottling up since childhood. The Blazing World is an attractive fantasy film, but a flawed one. It’s attractive in a sensory way, charming us with lush imagery and a rich sound design. The story, however, is more distancing than attractive, and it gets stuck under the weight of heavy-handed and self-indulgent psychoanalytic themes. Young was inspired to write The Blazing World after reading Margaret Cavendish’s 1666 book of the same name. She first developed a short version of the film, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2018, before returning to the festival in 2021 with the feature-length version. In her director’s statement, Young writes that The Blazing World is about the “transformation of consciousness.” Indeed, the basic conflicts of the story feel like they were plucked out of a psychoanalysis 101 textbook. Margaret’s troubles begin with the death of her twin sister (her perfect reflection or ideal self, you might say), who passes away at a young age. As an adult, Margaret becomes the reluctant mediator between her alcoholic father (Dermot Mulroney) and neurotic mother (Vinessa Shaw). Margaret returns home from college one weekend to help her parents move out of their enormous house. While walking around her parents’ yard at night, Margaret falls down a “rabbit hole,” so to speak, and enters a parallel universe. Here, she comes face to face with a man who has been haunting her dreams since the death of her sister. The man (Udo Kier), who introduces himself as Lained, tells Margaret that her sister is being held captive in this parallel universe by three demons. If Margaret can obtain a key from all three demons, she’ll be able to bring her sister back. It comes as no surprise that the first two demons are versions of Margaret’s father and mother. The “mother” demon complains of loneliness and demands that Margaret leave a piece of herself behind in exchange for the key. The “father” demon delivers a tiresome monologue about his manly burdens and the roots of his rage. There’s nothing wrong with exploring Freudian mommy and daddy issues in a narrative film, but the oversimplified nods to psychoanalytic theory suck the life and creativity right out of The Blazing World. Plus, Margaret isn’t dynamic enough to support a story about the development of consciousness. In trying so hard to show us that Margaret is a traumatized, absent-minded, aloof, quirky, and misunderstood young adult, Young creates a wishy-washy character who’s more of a personification of teenage emotion than an actual person. Margaret’s emotions are theatrical and misplaced, making it difficult for us to relate to and sympathize with her. The Blazing World is all the more frustrating because it has such stylistic potential. The movie begins with a seductive opening sequence that sets the bar high. The opening credits roll over a wispy pink background as a mystical harp melody plays, letting us know that the feature to follow is undoubtedly a feminine fantasy. Then, we see a flash of solid pink before the film cuts to a wide shot of twin girls catching fireflies. A selection from “The Nutcracker” begins to play, and the girls exchange whispers as they run around a tree and fill their jar with fireflies. Meanwhile, their ultra-cultured parents begin arguing inside the family’s extravagant mansion. The mother accidentally cuts herself while chopping vegetables for dinner, and a closeup shows sparkling red blood oozing down the silver knife. The arguing intensifies. Moments later, one of the twins falls into the pool and drowns. Similar to the opening of Melancholia (2011), this sequence combines elements of fantasy and reality to set the mood and foreshadow the inevitable decay of upper-middle-class materialism and family values. And, like von Trier does in Melancholia, Young uses the opening sequence to choreograph tragedy as a beautiful work of art. Processing tragedy in front of a public audience through art is always a risk. One person’s cathartic release can be another person’s trigger. There’s certainly a lot of grey area when it comes to the ethics of showing traumatic events on screen. I wouldn’t say that Young crosses the line during the opening sequence of The Blazing World, but she definitely takes things one step too far during the climax of the film. In order to obtain the third key, Margaret must metaphorically end her life. She does so in a graphic and explicit manner, and the camera spares no detail. The questionable scene cheapens Margaret’s already weak emotional development, glorifying self-harm as a necessary means to overcome trauma while also belittling the reality of suicidal ideation. Portraying suicide as a self-defining act of strength is always a bad idea. There’s a time and a place for metaphor, but using explicit self-harm as a metaphor is a risk not worth taking. Still, Young shows lots of promise as a first-time feature director, demonstrating passion, determination, and creativity. She’s able to develop a specific tone through memorable visuals, and she has a firm grasp on style. While it’s clear that the process of writing The Blazing World was personal and therapeutic for Young, the final product is too personal, like a diary entry that’s not supposed to be read by anyone but the author. Despite the film’s technical beauty, the story lacks the narrative nuance needed to support the themes Young wants to explore.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|