|

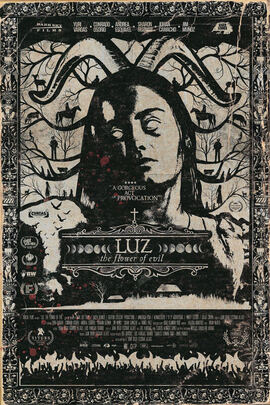

Originally published on Elements of Madness  Last year, Ari Aster set the bar high for “daylight” horror films with Midsommar, a terrifying fantasy that casts its disturbing events against a beautiful, blossoming, sunlit backdrop. The genre-play proved to be quite successful for Aster, although the effect is not so much scary as it is genuinely disturbing. Fans of Midsommar will find a somewhat similar effect in Luz: The Flower of Evil, a folk-horror fantasy from writer/director Juan Diego Escobar Alzate. Combining the narrative elements of religious-cult horror films such as The Other Lamb (2019) with the vibrancy of Midsommar, Luz: The Flower of Evil is a stunning and layered exploration of faith, evil, and the search for meaning. Three sisters, Laila (Andrea Esquivel), Uma (Uri Vargas), and Zion (Sharon Guzman), who are considered perfect “angels” in their mountain village, are deeply heartbroken over the loss of their mother, Luz, and are searching for answers as they reach maturity. Their father, referred to only as “El Señor” (Condrado Osorio), serves as the patriarch and spiritual leader for the village. He keeps hope alive with fiery sermons warning against the disguises of the devil and the promise of the coming of a messiah who will bring prosperity to the village. However, it is soon revealed that in the years since his wife’s death, El Señor has already brought several young boys to the village and named them “Messiah,” only to dismiss them soon after when they failed to provide the right signs and miracles. The villagers, including his three daughters, are beginning to lose faith in El Señor, even as he brings the next young “Jesús” (Johan Camacho) to the village, quite against the child’s will. Instead of a new season of peace and prosperity, the coming of this messiah brings sickness, evil, and terror, consequences that El Señor refuses to take responsibility for. Luz takes its time getting to its climaxes and revelations, relishing the thoughts and spiritual musings of its three heroines in poetic voice-overs. Luz relies much more on imagery and cinematography than plot and can, therefore, feel slow. However, it fills each moment with deliberate images that could stand alone as works of art. The opening credits sequence is like walking through a realism display at an art museum that foreshadows the film’s coming terror. The montage of blood and bones, illuminated by bright, natural light, is more than a bit sickening, serving as a reminder that horrific things can happen in any time and place. However, with a Mozart clarinet melody floating among these images, and with a grainy texture that puts the spectator at a distance from the animal carcasses and bloody sheets, there is also a thick haze of tranquility. The texture, vibrancy, and score set a peaceful tone, and, despite El Señor’s attempts to intimidate his daughters, allow the film to radiate a life-giving energy throughout. The beauty and naturalism of Luz mock El Señor’s villainy, making him much less menacing, although still quite believable as a villain. To be sure, Luz does get gruesome, and this peaceful tone by no means belittles the pain that El Señor inflicts upon his daughters nor diminishes the seriousness of his violent acts. Instead, Luz’s beauty creates a sense of hope and protection, suggesting that the three women are stronger than El Señor’s insanity. While Luz fits quite nicely into the “folk horror” label, it is much more complex than the average folktale, which can often succumb to heavy symbolism and overused character tropes that simply represent a binary of good and evil. In Luz, even the villainous El Señor represents more than just pure evil. He undergoes painful internal conflict, revealing traces of the good father he could have been. He expresses intense grief and a crisis of faith, demonstrating how evil actions come about through the unhealthy handling of emotions and warped perceptions of reality. Similarly, Laila, Uma, and Zion are not just symbols of pure innocence who have been inexplicably brainwashed by a fanatical religious patriarch. They are grieving the loss of their mother, and as they constantly struggle against nature to work the land and produce enough to survive, it makes sense that they are looking for answers in El Señor’s false prophecies. But they are also discerning and thinking women, each with their own nuanced faith that has been shaped by their experiences. Uma, for one, is totally skeptical of El Señor from the beginning, and all three of the women seem much more enamored with their deceased mother than their father, as if they would leave El Señor’s cult in a heartbeat if their mother were to somehow magically return. Beyond its characters, who overcome symbolic binaries with their nuances, Luz is filled with religious and literary symbols that defy expectations, from the tape recorder that Laila finds in the woods to the goat that creeps around the village at night. However, Luz does not rely on the spectator’s shared understanding of these symbols to give the story its importance and meaning. In fact, in both style and plot, Luz is about overcoming the need to endow symbols with unnecessary meaning. It is about letting go of the need to find an easy explanation for good and evil and instead embracing the unpredictability and inexplicable nature of life. El Señor demonstrates this need for meaning when he repeatedly selects random children to be the messiah. Lost in grief and desperate for simple explanations and control, El Señor demands answers from the totally disinterested child, who perhaps, in the end, has absolutely nothing to do with the horrific events that haunt El Señor and his family. Luz succeeds in its fantastical realism because it doesn’t rely on magic, complex folklore, or recognizable symbols to explain its events. Instead, it allows the characters themselves to create meaning with their unique desires, strengths, and flaws. Available on VOD now. Final Grade: A

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|