|

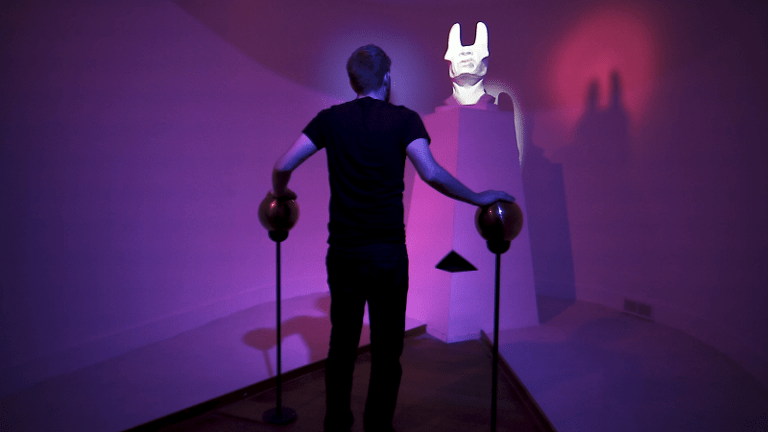

Originally published on Elements of Madness  If you spend time with kids on a regular basis, then at some point you’ve probably been asked to play a confusing game with vague rules and unclear objectives that the kids invented themselves. It might be a live-action-role-playing-game that ineffectively combines mythology from a smorgasbord of fairy tales and video games, or perhaps a board game where the rules change every five minutes depending on whether the young game-maker is in the lead. Of course, we don’t expect children to meticulously plan out alternate worlds with consistent themes, and their creativity is endearing, even if we are subjected to hours of games that make absolutely no sense. But now, imagine that the neighborhood kids made a documentary explaining a game that they invented together. They haven’t quite agreed on the rules yet, and each kid has a totally different vision for the game, yet they have decided to make a film explaining it. If you can imagine this sort of film, filled with interviews from people who all have different ideas about the same game, then you’ll know what to expect from In Bright Axiom. Directed by Spencer McCall, this ambitious documentary explores the strange and experimental Latitude Society, an artistic project that was part spiritual group and part live-action-role-playing-game. If you don’t have background knowledge about the project, however, In Bright Axiom will send you into a hole of internet research as you try to make sense of its absurd details. In Bright Axiom is McCall’s second film to document the “urban playground” experiments of entrepreneur Jeff Hull and his entertainment business/artistic studio, Nonchalance. The Latitude Society was a Nonchalance game disguised as a cult-like secret society where members could create meaningful connections and escape the drudgery of everyday life through meditation and play. In Bright Axiom uses a combination of reenactments and member-interviews to illustrate the society’s induction process, its various escape-room-like quests and missions, and its activities and retreats that encouraged members to open their minds to new creative possibilities. The creators at Nonchalance kept the real nature of the Latitude Society fairly secretive, and, as In Bright Axiom suggests, some society members seemed to think that they were, in fact, part of an authentic spiritual-enlightenment group that had been around for decades. Operating on a strict policy of “absolute discretion,” Latitude Society members were not supposed to talk openly about the group or post about it online. In its second half, the film turns to exploring the consequences of Hull’s experimental game, documenting how the society slowly fell apart as tensions arose between Hull’s business goals and the members’ growing feelings of society ownership. Taking its name from a common society greeting, In Bright Axiom seeks to recreate the sense of fear, wonder, and eventual disillusionment that characterized the Latitude Society experience. In order to accurately represent that experience, In Bright Axiom reveals information about the Latitude Society slowly, withholding the backstory about Jeff Hull and Nonchalance until much later in the film. The film’s format is clever and intriguing, and when done correctly, this sort of performance-art film could effectively convince its audience that they are watching a factual documentary, only to drop a major plot-twist halfway through. However, In Bright Axiom fails in this genre experiment because it withholds too much information and never succeeds in convincing its audience of anything, whether fact or fiction. The details about the Latitude Society are so frustratingly vague that without prior knowledge of Jeff Hull and Nonchalance, the film is almost entirely inaccessible. In the first half of the documentary, it seems that each person is talking about a completely different experience rather than a single secretary society. In the second half, there is neither a straightforward explanation about Nonchalance nor a clear transition to signal that the documentary has shifted into an examination of the Latitude Society as a game invented for business purposes. The audience is therefore left in total confusion, as if trying to piece together instructions to a game invented by kids who never really agreed on the details. The main factor causing this confusion is that In Bright Axiom lacks both context and cohesion. None of the interviewees are identified, and there are no clear transitions between interviews with people who work at Nonchalance and interviews with ordinary society members. This creates inconsistencies in the discourse surrounding the society and leaves the audience to wonder why each person interviewed seems to be talking about something totally different. Even in the first portion of the film, when society members discuss their inductions and experiences, In Bright Axiom seems like a montage of clips from 10 different documentaries about 10 different secret societies rather than a single, cohesive film about one group. One member might talk about the group as a creative space for art to be produced, while the next might talk about it as a religious experience that created community. One clip might show vintage arcade games that may or may not be part of the initiation processes (their symbolism is never explained), while the next clip might suddenly throw in animal masks that seem to be symbols of a totally different society. If anything, this lack of cohesion perhaps reflects a similar sense of confusion in the Latitude Society itself, where members developed vastly different ideas about the society’s purpose. Vague goals may not be so much of a problem in a startup secret society where members do not meet in-person very often, but a documentary needs context and cohesion to convince its audience that this experimental, art-performance-game actually succeeded in recruiting members. In Bright Axiom is also desperate for a narrative voice to pull everything together. In a documentary about a society that was so vague and difficult to define, there needs to be some kind of narration to provide context for the seemingly unconnected interviews and reenactments. Instead, In Bright Axiom simply lumps these clips together with no transitions. There is no narrational voice-over and no sense of the filmmaker’s presence (McCall does make an appearance later on in the film, but his brief on-screen appearance only opens up more questions). This lack of narration may have been an intentional genre experiment. Just as new members of the Latitude society didn’t initially know about Jeff Hull or Nonchalance, we aren’t supposed to know who is behind this film or how the director got members of a society of “absolute discretion” to talk to him. But, again, In Bright Axiom is so lacking in context that it doesn’t work without a narrative voice. Like a game invented by a group of kids, In Bright Axiom gets points for ambition and creativity. A few of the reenactment sequences could stand alone as colorful, hypnotic, and mind-opening shorts, but as a whole the film is desperately missing a cohesive thread. It’s difficult to tell if In Bright Axiom was, in fact, meant to represent the Latitude Society experience to the general public, or if it’s just a private joke for those in-the-know. Either way, In Bright Axiom gets lost in its ambition and presents the Latitude Society as an under-planned, unfinished, and confusing experiment that not even its creators can explain. Grade: C-

1 Comment

|

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|