|

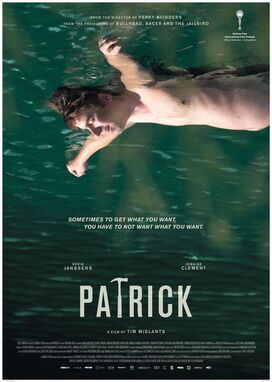

Originally Published on Elements of Madness  One of film’s unique narrative strengths is the camera’s ability to manipulate perspective. A movie can put us behind the mask of a serial killer on Halloween or on the tip of a shark’s nose just before it attacks. Point-of-view shots are both riveting and revolting. They force us to confront stomach-turning visuals, and yet, as we share the perspective of a character who we care about, we can’t turn away. In the case of Patrick, a selection from this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival, cinematographer Frank van den Eeden capitalizes on the power of perspective to create a detailed and accessible portrait of the emotionally unavailable title character. Patrick is a stylized, darkly comedic thriller that hones in on the anxiety of its antisocial protagonist, exposing (in more ways than one) the ridiculousness of the world around him. Patrick is a quiet, distant man who works as a handyman at his parents’ campsite. Their nudist campsite, that is. While he doesn’t have much to say and the campers treat him like a child, he is a fantastic carpenter who enjoys building furniture when he’s not helping out the entitled guests. When his favorite hammer goes missing from his workshop, Patrick is deeply disturbed by its absence and resolves to find it. Before he can get started with his investigation, however, his father suddenly passes away. The campers express (and feign) sympathy as they begin to question Patrick, who has now inherited the camp, about the future of their beloved vacation spot. There’s even a plot brewing to take the property away from Patrick, but his one-track mind can only focus on the mystery of his missing hammer. At first glance, the plot summary seems like that of a goofy comedy. Patrick is certainly full of dark, satirical humor that makes fun of the nudist campers, who are a hilarious blend of commune hippies and well-to-do retirees with their pearls and boating shoes. However, with a dry comedic style that’s reminiscent of films like The Lobster (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2015), Patrick also asks its audience to take it seriously. Patrick is a story where childlike emotions take center stage in a world filled with grown-up, “mature” concerns. It is so powerful because it validates Patrick’s irrational obsession and allows the audience to share his intense frustration over something that should be trivial. While the guests at the campsite worry about death, money, property, and relationships, the film asks us to empathize with Patrick instead and to understand the stakes of the missing hammer in the same way he does. By centralizing Patrick’s irrational quest, the film illustrates not just grief, but general anxiety. In the same way that Melancholia (Lars von Trier, 2011) illustrates depression by minimizing an apocalypse through the eyes of a character who is more than prepared for the world to end, Patrick illustrates anxiety by maximizing an irrational problem through the eyes of a character whose consciousness we come to share as spectators. The question is, then, how exactly Patrick turns that irrational quest into a serious narrative problem. As already noted, one of the film’s most notable successes is the cinematography, which allows us to identify with Patrick. At times, the camera moves with him through crowds of pesky, meddling campers, demonstrating how he sees the social world around him as an obstacle. During these moments, we feel Patrick’s claustrophobia and urgency. There are also times, however, when the perspective of the camera seems dark, menacing, and untrustworthy, and we begin to question whether we should be afraid of the shy and lovable protagonist we’ve been rooting for. Patrick is one of those films where the camera itself becomes a secondary character, lurking frustratingly out of view and creating a haunting, unseen presence. As Patrick stomps around the camp with unwavering intensity in his eyes, searching for the hammer thief, it seems that a moment of violence is always just around the corner. As he gazes across rows of wrenches and screwdrivers at a shop, we begin to wonder if perhaps Patrick is choosing a weapon rather than picking out a new carpentry tool. Actor Kevin Janssens creates a powerful yet awkward screen-presence for Patrick, a presence that reflects some of cinema’s most infamous villains such as Michael Myers, Norman Bates, and Boris Karloff’s embodiment of Frankenstein’s monster. Shadows of these classic villains haunt Patrick’s character and, despite his childlike innocence, make us question his intentions. Patrick captivates its spectators by creating a strong presence for its title character that we must take seriously, whether we are scared of him or sympathize with him. Patrick also centralizes the protagonist’s anxiety with a single visual motif: a shot of the wall in Patrick’s workshop where all his other hammers are nestled in hammer-shaped nooks with a space for the missing hammer catching our eye in the center. This repeated shot creates tension and longing, an irksome and unsatisfactory image that burns from the screen and makes us feel Patrick’s passion for his beloved missing hammer. The negative space where the missing hammer should be is maddening, allowing it to take on emotional weight. Depending on the context of the scene, this repeated image can represent not just grief, but also anxiety, sexual tension, and isolation. By repeating the shot at precise instances, Patrick allows the missing hammer to become much more important than the “grown-up” issues that bother the campers. This shot illustrates how anxiety can be, for many, quite overwhelming. The persistent sense of a looming, violent presence created by the camerawork and the relentless visual motifs give Patrick the flair of a complex, epic thriller despite its fairly straightforward plot. The film also packs a minimalist comedic script, written by director Tim Mielants and co-writer Benjamin Sprengers, that complements the strange satirical world of the nudist camp. Alongside Janssens’s sympathetic Patrick is Pierre Bokma as the slimy, perverse Herman, a subtle villain whose feigned sympathy for Patrick is enough to make anyone’s skin crawl. The one flaw worth mentioning in this review is Patrick’s attraction to Nathalie (Hannah Hoekstra), a woman who visits the camp with her neglectful, emotionally abusive boyfriend, a predictable plot-point that sticks out like a sore thumb in this satirical thriller. The manic pixie dream girl doesn’t fit the overall tone of the film, and, unless she was given more dynamic development, she is not necessary for Patrick to work out the way that it does. Patrick and Nathalie’s friendship remains on the fringes of the narrative, however, and doesn’t distract from Patrick’s beautiful portrait of an anxious person’s emotional experience in the world. In the end, the film’s profound attention to detail makes it a cathartic, must-see experience. Currently screening during the 2020 Fantasia International Film Festival. For more information, visit the 2020 Fantasia Film Festival website. Final Grade: A

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|