|

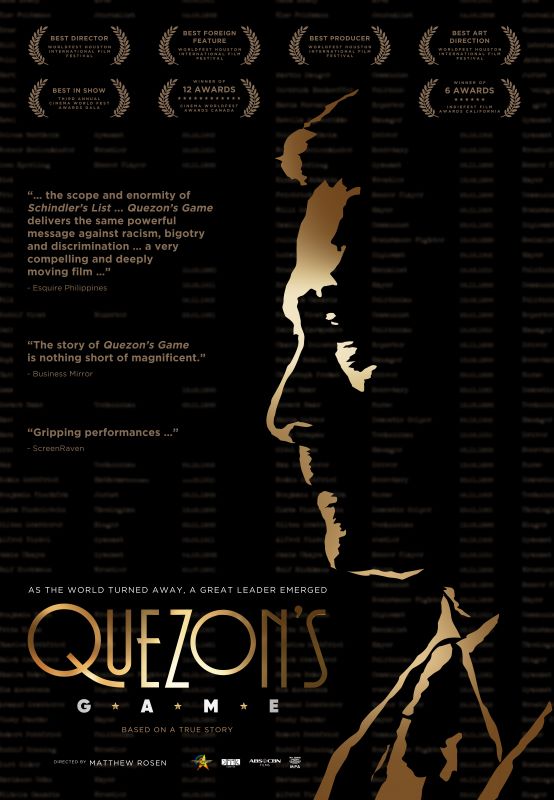

Originally published on Elements of Madness As early as 1945, two years before the liberation of Auschwitz, filmmakers began to grapple with the challenge of preserving Holocaust memory on screen. Directors like Mark Donskoy and Wanda Jakubowska took great risks with their films, The Unvanquished (1945) and The Last Stage (1948), respectively, which were some of the first to depict the mass violence of the Holocaust. Since the release of these early films, directors have continued to use cinema to preserve Holocaust memory and honor victims, survivors, and those who risked their lives to help. With the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz on January 27, 2020, it seems there are still more stories to tell about these events, stories and perspectives that have yet to be explored on the big screen. When director Matthew Rosen learned of one such story, that of former president of the Philippines Manuel Quezon and his efforts open the borders of his country to Jewish refugees, Rosen decided to bring the narrative to the screen with his feature film debut, Quezon’s Game. Rosen’s historical drama opens on a weary Quezon (Raymond Bagatsing) and his wife, Aurora (Rachel Alejandro), in 1944, watching a newsreel and reflecting on the inhuman terrors of the death camps. Looking defeated and hopeless, Quezon turns to his wife and asks, “Could I have done more?” His haunting question launches the narrative and sends the story back six years in time. In 1938, Jewish-American businessman Alex Frieder (Billy Ray Gallion), who is living in the Philippines with his brother, gets a disturbing telegram from a German contact. Panicked and afraid, Alex relays the message to Quezon and his political allies over a game of poker, earnestly asking Quezon to open the Filipino border to Jewish refugees. Although the most ethical choice seems clear, for Quezon, it’s not as simple as that. The Philippines have not yet secured independence, so Quezon and his associates face a stronghold of political red tape and legal battles. As Quezon fights to save thousands of lives while juggling domestic issues, his family, and his own health, the film continually returns to his opening question, asking how much one person can do in the face of powerful systems of terror. That opening question reflects a similar line from one of the most well-known Holocaust films (at least among American audiences), Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. Toward the end of this film, as Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson) looks at the crowd of people that he saved, he repeatedly says, “I could have got more out.” Indeed, it’s almost too easy to compare Quezon’s Game with Schindler’s List as the films share similar plots and themes. Quezon’s Game differs in two significant ways, however, allowing it to stand out as a unique story in the realm of Holocaust films. First, Quezon’s Game does not seek to preserve Holocaust memory through traumatic images, as do many other films including Schindler’s List. Save for two or three newsreel scenes, the film forgoes images of camps and ghettos and instead dramatizes behind-the-scenes political logistics. The film’s structure is built upon scenes in which key players huddle over drinks in dim rooms, enacting precarious deals or parsing out how to make their next move. All the while, thousands of suffering people wait for an answer. We do not see them on screen, but we feel their presence nonetheless. Quezon’s Game thereby succeeds in highlighting the fierce obstacles that often stand in the way of obvious ethical choices, asking us to reconsider our own priorities when we have the opportunity to help those who are suffering. Second, Quezon’s Game differs from other Holocaust films like Schindler’s List as it honors not only one person’s efforts to save lives, but the collective efforts and the merciful spirit of an entire country. As Aurora says several times throughout the film, Quezon’s greatest strength is his faith in the Filipino people. Quezon is challenged and moved to help the refugees as he realizes that his people, too, suffer from racial prejudice. He is inspired by the strength and spirit of the people in his own country as he fights his political battles, and he eventually turns to his people for help. Rosen, by choosing this story for his film, honors not only the story of an individual but also the history of a country that, despite lacking independence, was willing to open their home to those who had even less. While Quezon’s Game illustrates a clear message and establishes unique themes, unfortunately this message is, throughout the film, too clear and quite forced. Rather than taking time to build emotionally-developed characters with complex problems, the film relies too closely on the assumption that the audience knows that this is supposed to be an emotional story and will react appropriately. The problem begins with the dialogue. The characters state their problems as facts and the audience is expected to know how to react to these facts. In one scene, for example, Quezon watches a newsreel that shows hundreds of Jewish refugees turned away at the American coast. Instead of reacting to the news, Quezon simply restates it. He turns to the character next to him and says, in a tone that reflects the overdramatic lines of a school play, “Can you believe that both America and Canada turned them away?” Much of the film is like this; the audience is pulled through what could have been a complex emotional journey with obvious dialogue. The result: an immature emotional tone that does not match the weight of the story. Along with this shallow dialogue comes stock characters that, unfortunately, the cast is not quite able to overcome with their performances. Quezon’s characterization is particularly unstable. We learn about him not by watching Bagatsing’s embodiment of the historical figure, but from flat factual statements as the other characters describe him. Details about Quezon’s personal life are unevenly plopped in throughout the film with side plots about his love life and health situated at the beginning and end of the film, respectively, and are never fully incorporated into his character. Similarly, the film sacrifices depth of characterization in Aurora for a sloppy message about family loyalty. Aurora, as the underappreciated but devoted wife, constantly reacts to Quezon’s choices with love and loyalty, but she lacks any unique characteristics of her own. She could be any devoted wife from any film about any powerful politician. In scenes where Aurora does stand up to her husband, the obviousness of her lines robs her of any agency, making her much more of a stock character than a strong individual woman. Despite these shortcomings, Quezon’s Game still tells a unique story of Quezon’s efforts and those of the Filipino people, who desperately tried to help when many others would not. The film further honors Holocaust memory in its end credits by incorporating interview clips with Jewish survivors who immigrated to the Philippines as children. The interviews tie the final knot between the semi-fictional world of the film and historical reality, allowing the survivors to play a part in the practice of storytelling. As these grateful survivors offers their thanks, the film offers an answer to Quezon’s haunting question, “Could I have done more,” by celebrating the incredible miracle of every individual life saved from violence and injustice.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|