|

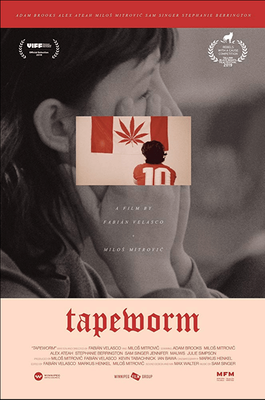

Originally Published on Elements of Madness The Slamdance Film Festival, which runs at the same time and in the same city as the more widely known Sundance Film Festival, gives new and aspiring filmmakers the chance to showcase their work in front of other industry professionals. With independent and low-budget films in the lineup, Slamdance has served as a starting point for many filmmakers who later went on to find immense success, including Christopher Nolan, Ari Aster, and recent Oscar-winning director Bong Joon-Ho (Parasite). Among the films presented this year was Tapeworm, the feature debut of co-directors Milos Mitrovic and Fabian Velasco. The Canadian filmmaking duo has worked together before on short films like Imitations, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2016. Collaborating again to write and direct, with Mitrovic acting as well, the two strike just the right tone with Tapeworm, a gritty and awkward comedy that turns life’s most ordinary and embarrassing moments into captivating vignettes. Tapeworm follows a handful of micro-plots as it casually drifts between the lives of its seven main characters: a middle-aged, self-absorbed hypochondriac who diagnoses himself with tapeworm; his live-in girlfriend, Gigi, who is visibly disgusted with every aspect of her life; a young couple who enjoys marijuana and sex in the woods; a failing stand-up comedian with depression; a loser video-game addict who still lives with his mom; and, of course, said mom, who cries and throws her freshly-bought eggs at the ground when her son refuses to help put away groceries. The story leaves a lot of room for guesswork about the relationships between these characters. Are Gigi and the hypochondriac man married, or just living together? Is it one of the other characters who lives next to them and makes all the noise at night? However, what’s more important to Tapeworm than these specific details is the characters’ emotional landscapes. While the characters’ narrative relationships are unclear, they are all connected by the shared emotions that color their everyday lives: depression, apathy, bitterness, and loneliness. Mitrovic and Velasco gradually pull the audience into these uncomfortable emotions with the grainy and nostalgic texture of 16mm film. Tapeworm is, at times, cozy and familiar, taking us to settings like a mom-and-pop diner. It is, at other times, surrealist, diverging from those comfortable moments to gory and upsetting images (a close-up of bloody human feces in a field, for example). Tapeworm’s day-in-the-life approach to its characters situates the film somewhere between cult-classic comedies like Clerks (Kevin Smith) and structure-bending film-school favorites like Jeanne Dielman (Chantal Akerman). The film is full of dull, everyday moments like folding laundry or sweeping up broken plates, but it expands and explodes these moments with anxiety-inducing extended shots and long periods of silence. When the silence is finally interrupted by dialogue, it is awkward and unsatisfactory, increasing the tension rather than resolving it. Yet, Tapeworm also finds its comedy in this tension, squeezing humor out of awkward situations. Much like the film’s failing stand-up comedian, who starts promising anecdotes that lead to flat and over-explained punchlines, Tapeworm puts its characters through such embarrassing moments that all we can do is wince and let out a few timid chuckles. Tapeworm revels in moments that are not necessarily comedic but that demand laughter from the audience just to ease the anxiety and discomfort, from poorly received gift exchanges to paranoiac confrontation. Unlike both Jean Dielman and Clerks, however, Tapeworm lacks a definitive climax. There are bursts of shock, such as freak injuries or interrupted intimacy, that do feel more jolting and even conclusive for the characters involved. However, the film goes right from these shocking scenes back to the mundane moments with little to no transition, like a series of hiccups. Mitrovic and Velasco effectively manage this structure by keeping their film short. Running at just 78 minutes, Tapeworm can keep the audience’s attention even without traditional rising and falling action. The short run-time does make it difficult, however, for Tapeworm to explore any one of its seven characters in depth. Although the film observes very personal moments in the lives of these individuals, we know so little about them that they emerge as worn-out stereotypes. They are more like a series of student exercises in characterization than fresh, well-rounded protagonists. In fact, while almost every technical aspect of Tapeworm is excellent, the film wobbles precariously between a memorable indie flick and a well-intentioned student project. At times the effort is a bit too visible, like a checklist for the perfect dark-comedy cult-classic. 16mm? Check. Awkward dialogue? Check. Quirky characters? Check. Unconventional narrative structure? Check. But Tapeworm lacks that special, unique factor to make it stand out. It is not a bad or failed film, by any means, but the characters and situations are all too familiar. And yet, Tapeworm is still riveting. It may not garner an energetic following or hold up as a classic, but it is thought-provoking and beautiful. Thanks to the talented cast, most of whom are unprofessional actors, the stereotypical characters in Tapeworm are still engaging. Adam Brooks’s heartbreaking confidence in lines like, “I think I have a tapeworm… and I’m going to keep it” gives his character that off-beat realism that makes similarly unconventional films work, redeeming his underdeveloped character. The actors are interesting and appropriately awkward, fully embracing their characters as societal outcasts who are deeply upset with their place in the world and haven’t quite figured out how to act around other people. The cast does the best they can with the story they are given, breathing life into otherwise stereotypical characters. While it may not be the most original work, Tapeworm is more than redeemed by its technical precision and authentic performances.

1 Comment

|

"Our embodied spectator, possibly perverse in her fantasies and diverse in her experience, possesses agency...finally, she must now be held accountable for it." Categories

All

|